ASC community members shine at coding showcase

ASC community members shine at coding showcase What does a medication reminder app for elderly people and a tool to… Read More

Women in our community withstand unimaginable hardship seeking asylum in Australia, often balancing work and family with experiences of trauma and long, complex battles for protection. They fight against a system designed to grind them down, with many waiting over 10 years for determination on their visa.

The reasons why women seek asylum are often gendered. Many flee sexual violence and gendered persecution in their home countries. And some continue to face these issues here, with family violence prevalent among those we support.

Despite the challenges, the women of the Asylum Seekers Centre community display remarkable strength and humility, and we pay tribute to them for #InternationalWomensDay. These are the stories of just a few, whose resilience doesn’t always make headlines on days like this but inspires us everyday.

Laleh is an Iranian national who arrived by boat to Australia in 2013. She was detained in offshore detention on Nauru, where she remained for a few years, until she was medically evacuated to Australia for mental health treatment.

Laleh spent three months in accommodation provided by the Government upon arriving in Australia, after which she was released into the community with a six month visa and no possibility to permanently resettle in Australia. Laleh was told to secure a job and accommodation, and to meet her living needs independently. Though her mental health was badly damaged by her time in offshore detention, she wasn’t offered treatment.

“During the lockdown, Immigration gave me three weeks to find a job and a new home. If I didn’t have your Centre, I don’t know what would have happened to me,” Laleh explains. “They gave me a six month visa and wanted me to find a job. They didn’t care about my mental or physical illness.”

Given Laleh’s vulnerable mental health and the limitations of having a six-months visa, she continues to find it incredibly challenging to find a job and be independent. Over the last ten years, Laleh had to find ways to survive while navigating policies that were never in her favour. The lack of government support, the financial distress and the amount of uncertainties in her life led to a heart attack in 2020 in her 30s. She constantly fears that it will happen again. She speaks of the loneliness of her situation, and the self-encouragement required to persevere.

“During this time, I’ve been more isolated, which means I have been with myself a lot, and having a lot of conversations with my mind. I learn to talk to my mind in a very nice way. When I explain to my mind that this is not its fault, it’s just a situation, my mind really believes in that. One point that keeps me alive is good conversations between myself and my mind.”

A year ago, Laleh put in an application to resettle in New Zealand. Despite multiple interviews, there has been no outcome so far. Although there is hope for Laleh, this long process has impacted her wellbeing. Laleh says that it has been a difficult journey, but she perseveres, dreaming she might have a safe place to call home. She finds hope and comfort in those who help her, including her support workers at the ASC.

“We always need someone to believe in us, with no judgement, to keep our minds well. You have been this person to me.”

“I came to Australia when I was 14. Now I’m 24.”

Though just 24, Shanthi has experienced more, and worked harder, than most people do in a lifetime.

Shanthi has never set foot in her home country. Her family fled a civil conflict before she was born, eventually coming to Australia by boat in 2013. Shanthi’s teenage years were shrouded in family difficulties and legal struggles, as she battled for a refugee visa. A decade on, she still waits on her application for protection, which has now stalled in the courts.

Despite the hurdles, Shanthi’s achievements are remarkable. After arriving, Shanthi learnt English in High School through an Intensive English Centre, before completing the HSC and gaining her drivers licence through a Salvation Army program. She has since obtained a qualification in disability care, started working part time and commenced a new course, all while raising a child and supporting her extended family – two of whom live with her.

“I have a Certificate IV in Disability, and I’m doing a diploma in community service now.”

She describes her day-to-day life as a “fight” as she manages work, study, family and the uncertainties of her visa application. Due to where she is in the legal process, there is no safety net for Shanthi and her family, and no access to financial support. She has to depend on her wits and her resilience.

“When I work, I forget those things and I focus on the work. When I’m not studying, not working, the visa comes into my mind. So I always keep myself as busy as possible,” Shanthi explains. “Even when I go home I think about my visa situation, what’s going to happen next, where I will be in the future.”

“When I see my son’s face, it all goes away.”

Things were even harder when her son was first born and her mum wasn’t around. Childcare was unaffordable, so she went to the Asylum Seekers Centre for support.

“When I came to Asylum Seekers Centre as a single mum, I didn’t have childcare support, because in those times my family wasn’t supporting the care for my son. So it was very hard for me to go to work, or to be financially independent.”

She dreams of one day going to university, but knows that she needs to financially support her family. This year they mark a decade spent in limbo.

“I want to be free from this uncertainty so I can move forward.”

Asked if she thinks she’s a powerful and resilient person, Shanthi hesitates at first, before answering decisively.

“I think I am… but I’m not sure… Yes, I am.”

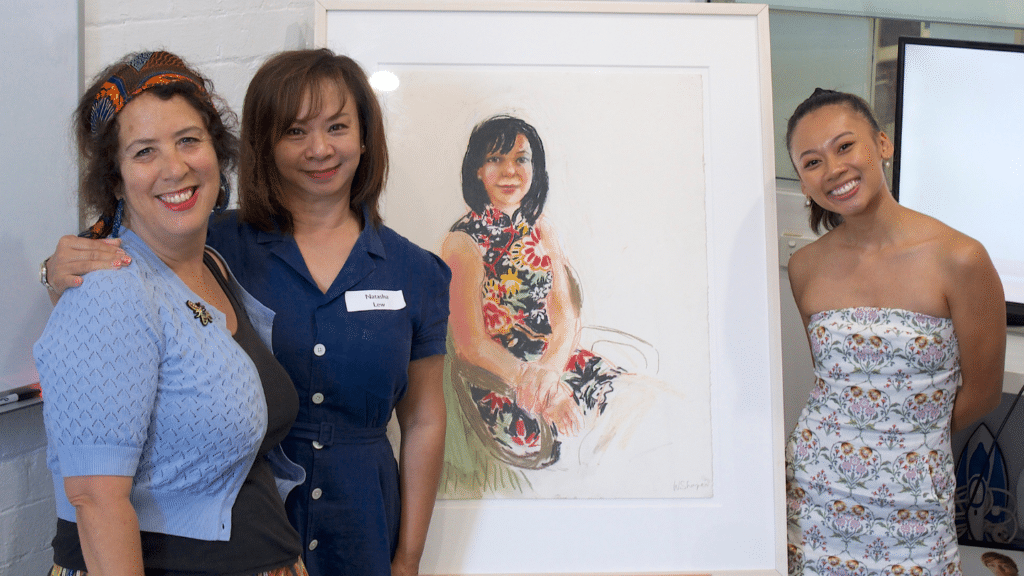

Fara came to Australia with her mother in 2013, fleeing a difficult domestic situation that put her at risk. She was 15 years old when they arrived. Her mum found out about the ASC searching online and Fara would join her mum for trips to the centre from their home in Quakers Hill.

“To her, the ASC was a place of refuge and safety. It made her feel seen and heard,” Fara explains. “And since the centre only opens on weekdays and I had school, I did what any good daughter would do. I skipped school to visit the centre. But only once!”

While they waited years for their visa to be processed, they would visit often. During one trip, Fara got talking to a paralegal who was working at the centre.

“She asked me what my favourite subject was at school and I said legal studies. And I remember her telling me that if I ever wanted to get into that sector, that I could contact her. Our interaction has impacted me to this day. Her belief in me was so genuine, even though she had just met me.”

Fara eventually finished high school, winning awards for legal studies, and with ambitions to go to university. Though, as they were on bridging visas, she would not be eligible for student loans and would be made to pay unaffordable international fees.

“My mum said she knew someone at the centre who knew someone from the scholarships team at Macquarie University. They encouraged me to write an appeal letter to Macquarie outlining my circumstances. I sent it off not knowing what would happen.”

In January 2016, Fara received a letter informing her that the university had agreed to sponsor her tuition fees until her permanent residency application was decided. They also provided a refugee mentor to help Fara adjust to uni life.

“I learned so much and gained so much experience,” Fara says about her first months at uni. “I was invited to speak at the University Open Day where I was able to share my experiences. It was really surreal.”

“Going to uni felt really far-fetched … but it actually became a reality for me.”

Soon after, Fara and her family were given their permanent protection visas. A few years into her degree, Fara started to identify her passion for refugee policy, so she too could help people through the complex and tortuous process of seeking asylum.

“I started to grow really passionate about helping refugees and people seeking asylum in uni. I studied a lot of units relating to refugee and immigration policy because I knew that was where my passion lies.”

Fara, now a citizen, proudly works in the same sector that supported her family and gave her a shot at University. She will never forget the challenges that her family went through, nor those who helped along the way.

*Names have been changed to maintain anonymity

ASC community members shine at coding showcase What does a medication reminder app for elderly people and a tool to… Read More

For decades, Australia has built a system of deliberate cruelty – one that governments around the world have copied. The… Read More

"*" indicates required fields